- No upcoming events

CELEBRATING WILLIAM BARTRAM

By Dorothy Smiljanich

Two hundred and fifty years ago, in April of 1774, a young man's travels took him to a site overlooking what we today call Paynes Prairie. Describing it as he saw it then, he wrote an entry in his journal that began: “The extensive Alachua savanna is a level green plain...” And with those simple words as his beginning and his subsequent fame in later years, he ensured our prairie a permanent place of honor in the long history of both literature and science.

Two hundred and fifty years ago, in April of 1774, a young man's travels took him to a site overlooking what we today call Paynes Prairie. Describing it as he saw it then, he wrote an entry in his journal that began: “The extensive Alachua savanna is a level green plain...” And with those simple words as his beginning and his subsequent fame in later years, he ensured our prairie a permanent place of honor in the long history of both literature and science.

For as the savanna was no common place, the man was no common man. His name was William Bartram, and he was only 35 years old when he came to this region and saw that “level green plain.” He had been born in 1739 in Kingsessing, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania into a rather patrician, well-educated, and highly accomplished family of the Quaker persuasion. By the time William and his twin sister Elizabeth were born, his father John Bartram was already a well-known botanist and naturalist who had traveled widely throughout the region (with even one foray into Florida in 1765 with William accompanying him) and who collected specimens and documented his findings in well received scientific papers.

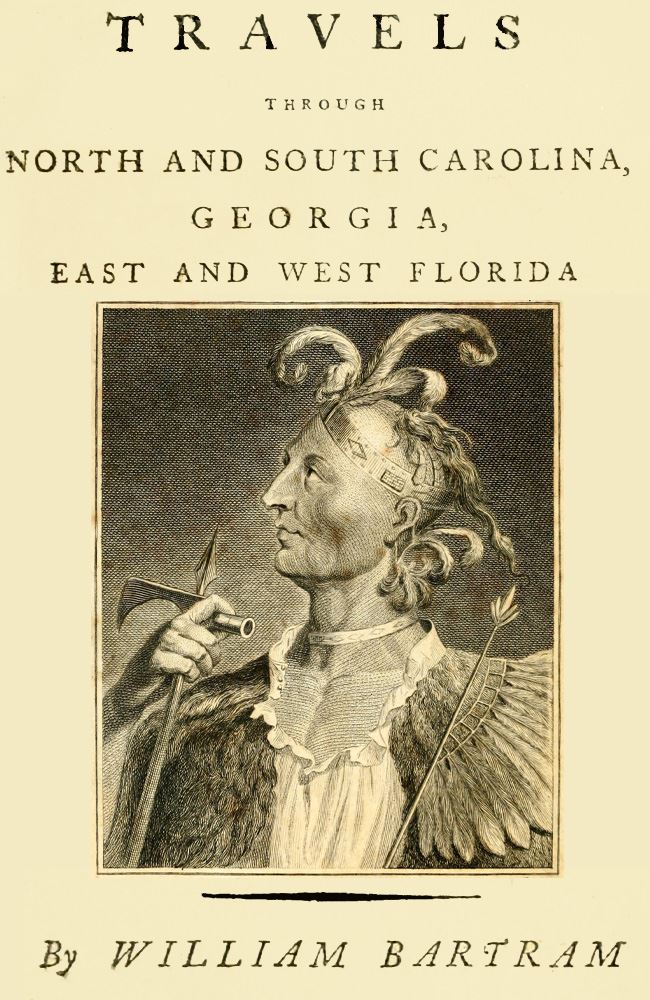

His father also was a member of the distinguished American Philosophical Society and in 1728, 11 years before William was born, John Bartram had created one of the first botanical gardens in the New World. Known today as Bartram's Garden, it is still operating in Philadelphia, as is the American Philosophical Society. His son William followed – quite literally sometimes – in his father's footsteps. But with all due respect to the elder Bartram, William surpassed his father's impressive achievements – mainly perhaps because William Bartram wrote a book based on the journals he kept during his travels. Its original marketing title when published in 1791 was “Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, east and west Florida, the Cherokee country, the extensive territories of the Muscogulges or Creek Confederacy and the country of the Chactaws: containing an account of the soil and natural productions of those regions, together with observations on the manners of the Indians.”

And in that book, familiarly known today as “Bartram's Travels,” William Bartram regaled the entire English-speaking world with his writing that was as colorful as it was erudite, as insightful as it was scientific. Back home in England, no less poets than Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth were entranced by his words. When Bartram began his travels in Florida in March of 1774, Florida was not a state, the United States was not a country and King George III and his Parliament were becoming increasingly displeased with their New World colony. The Boston Tea Party on Dec. 16, 1773, had been a shot across their royal bow and the First Continental Congress had convened (where else but in Philadelphia?). Against this contentious backdrop and while Daniel Boone was exploring the wild country west of Virginia and Capt. James Cook was exploring the South Pacific, William Bartram headed south, through South Carolina, Georgia and finally into Florida. His travels took him to many places in this region that we now call home. He drew sketches of them, he wrote about them, and he thus immortalized them all. To dip into his long and sometimes florid book is to immerse yourself in a world of wonder and adventure, beauty, and danger.

And in that book, familiarly known today as “Bartram's Travels,” William Bartram regaled the entire English-speaking world with his writing that was as colorful as it was erudite, as insightful as it was scientific. Back home in England, no less poets than Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth were entranced by his words. When Bartram began his travels in Florida in March of 1774, Florida was not a state, the United States was not a country and King George III and his Parliament were becoming increasingly displeased with their New World colony. The Boston Tea Party on Dec. 16, 1773, had been a shot across their royal bow and the First Continental Congress had convened (where else but in Philadelphia?). Against this contentious backdrop and while Daniel Boone was exploring the wild country west of Virginia and Capt. James Cook was exploring the South Pacific, William Bartram headed south, through South Carolina, Georgia and finally into Florida. His travels took him to many places in this region that we now call home. He drew sketches of them, he wrote about them, and he thus immortalized them all. To dip into his long and sometimes florid book is to immerse yourself in a world of wonder and adventure, beauty, and danger.

In fact, the names of the people, places and things he saw in this area are a resonating chorus familiar to us even 250 years later: the St. John's River, Palatka, Cowkeeper, Cuscowilla and, of course, Puc Puggy- “Flower Hunter” - his own nickname given to him by a Seminole chief with the explanation as Bartram wrote that the chief had “declared himself my friend and protector when he told me that if ever occasion should offer in his presence he would risk his life to defend mine or my property.”

No doubt many a Paynes Prairie camper has been befuddled by the name of the campground!

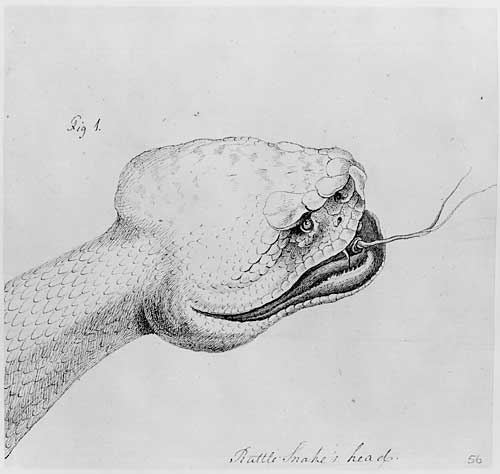

Bartram wrote at great length too about the wildlife, the plants, the birds, the alligators, violent storms, rattlesnakes, cattle, horses, and yes, of course, the Native Americans, noting, “I was a sincere friend of the Siminoles (cq).”

Bartram wrote at great length too about the wildlife, the plants, the birds, the alligators, violent storms, rattlesnakes, cattle, horses, and yes, of course, the Native Americans, noting, “I was a sincere friend of the Siminoles (cq).”

Wherever he traveled, he carried with him the Quaker virtues and core principles of Simplicity, Peace, Integrity, Community, Equality and Stewardship. This gentle, brave, and gifted man moved as nimbly among merchants, soldiers, rascals, traders, and Indians as he did the birds, the wildlife, and the plants. As we celebrate the 250th anniversary of his visit here, we might contemplate the words with which he begins an early chapter in “Travels:”

“We are, all of us, subject to crosses and disappointments, but more especially the traveler; and when they surprise us, we frequently become restless and impatient under them; but let us rely on Providence, and by studying and contemplating the works and powers of the Creator, learn wisdom and understanding in the economy of nature, and be seriously attentive to the divine monitor within. Let us be obedient to the ruling powers in such things as regard human affairs, our duties to each other, and all creatures and concerns that are submitted to our care and control.”

William Bartram left Florida forever in November of 1774 and returned home to turn his journals into a manuscript, catalog his botanical and ornithological collections, and care for his father's botanical garden. A lifelong bachelor, he died on July 22, 1823, at the age of 84 in Philadelphia.

Today, if you stand on any of the sites overlooking Paynes Prairie, from the La Chua Trail to the Visitors Center tower, from Bolen Bluff to even the boardwalk off US Highway 441, much of what you will see he saw 250 years ago – the level green plain abides, of course, and many of the same animals, plants, and birds. But of course, the traffic passing on US 441 or on I-75, and the development pressing in on all sides, he would not – mercifully - have seen. And perhaps saddest of all that he saw that we do not see are the Seminoles themselves, gone now perhaps but their lives and ways as they lived them here are immortalized in his work. So let the festivities begin!

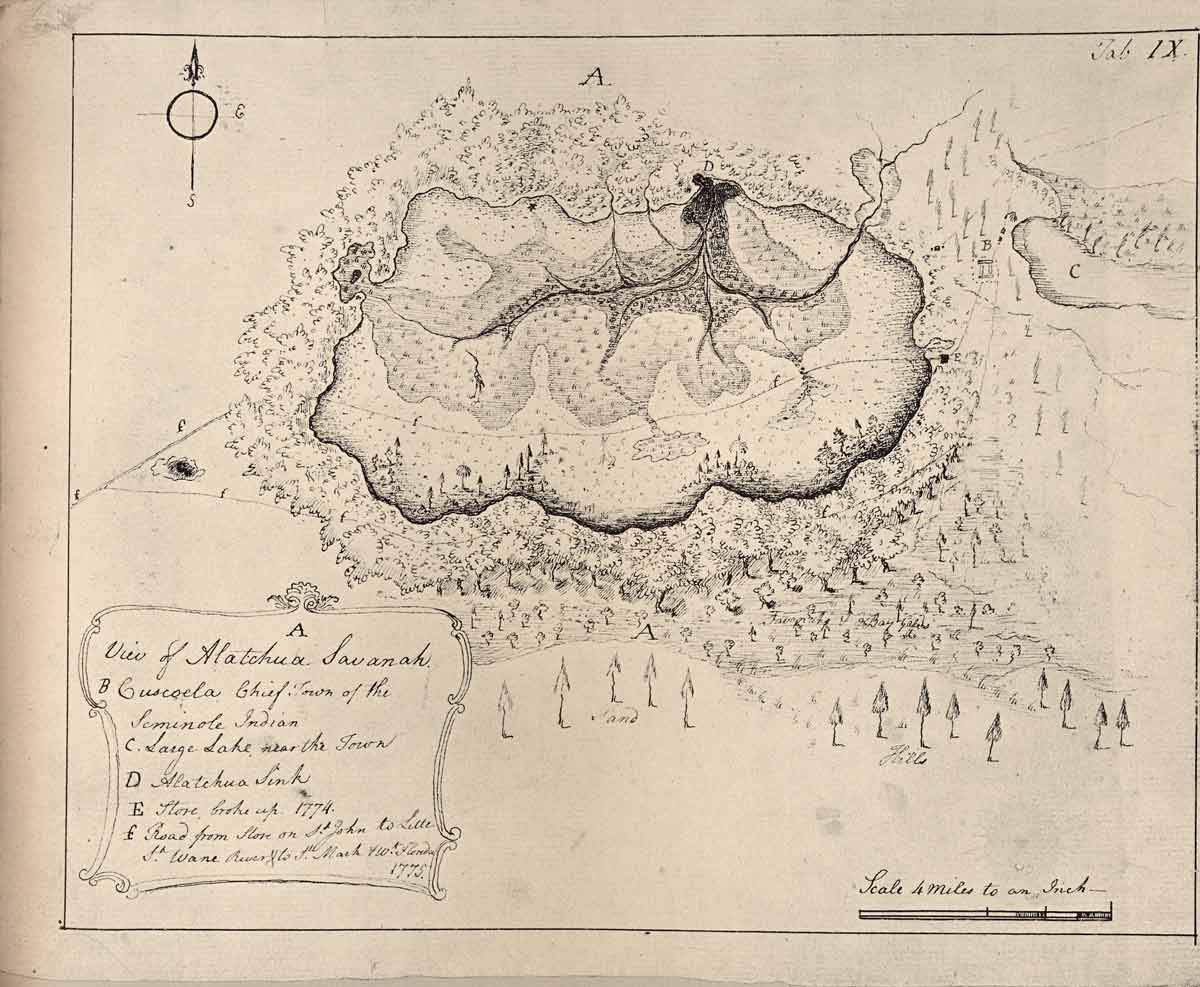

Bartram's map of the Alachua Savannah known today as Paynes Prairie.